|

| A bit of old draft attrib photostever |

Doing other stuff today and writing on the WIP, I came across a bit of

Spymaster's Lady that didn't make it into the manuscript.

So I figgered -- I'm never going to use this. Let's post it on the blog and maybe somebody can get something out of it.

This piece would have fit in the part of the story where Annique and Grey are first entering London. Instead of passing through Covent Garden and heading off to Meeks Street, they stop for a while. In this early draft version, Annique was going to write something important at this point. That disappeared in a later draft.

The fictional locale -- this tavern -- continues to exist in the Spymaster's fictive world. It just hasn't made its way into a book yet.

****

|

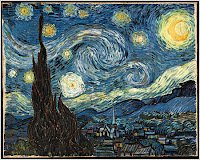

| Covent Garden |

ETA this first paragraph.

She had slept, on and off, through the night and the early morning while Robert, and the horse Harding, brought her all the way to London. She awakened suddenly in the dawn to the sound of wagons on cobblestones and women in white kerchiefs selling ladles of milk from the huge cans on the back of their carts. The sky was still pink when he brought her into the Covent Garden, which was not a garden at all but instead a market of incredible size, full of flowers and vegetables and chickens in cages, complaining.

In a street to the side of the market was the tavern called the Crocodile, which from the look of it was an accustomed meeting place of smugglers and other clandestine types. They knew Robert well, but did not once say his name or look at him directly or ask for payment. It was only 'Yes, Sir,' and they brought him ale to drink and a meal of beef which was a loathsome habit in the morning and thoroughly English.

For her, by some miracle, they conjured up black coffee in a tin pot and fresh rolls, so she was ready to forgive them as much as they wished. She allowed Robert to gift her with that coffee and another meal later in the morning. She did not have the strength to argue with him any longer, being disheartened and frightened by what she was about to do.

He was an even more important smuggler captain than she had realized. He sprawled at the end of the bench, his feet propped up, his back to the wall, his coat lapped about him, and dozed all the long morning. Men of all types and degrees, and a few women, came and went from the tavern. Not one glanced in his direction. Only important men can be so anonymous.

He made her safe there, from the denizens of that place and from those far worse who lurked in the streets outside. In safety, she could perform the next step in the great task she had set herself. She chose her spot, near the window where the light was good, and wrote and wrote and wrote in the small black book she had bought.

She held it now. To buy a blank-papered exercise book and ink and quills and blotting paper had consumed three and tuppence. But that was not in any way the cost of the book she turned over and over in her hands.

"I did not know I would be this afraid," she said. "Or that I would be ashamed."

Robert stood beside her with his arms crossed. It was as if he were on watch while some smuggled cargo was landed – alert and focused and awaiting events. The horse Harding would have been more inquisitive.

********

ETA: This out-take above slid into another, also not used. So I will add that. Two out-takes for the price of one. Hey. Such a deal.

Anneka, in this draft, is carrying a coded book to England. She has promised Adrian to drop it off at Meeks Street. As part of her own plans, she is doing that.

In the later draft I simplified the story and eliminated the whole six- or seven- thousand word subplot. Aren't you glad?

*****

She held it now. To buy a blank-papered book and ink and quills and blotting paper had consumed two pounds, ten, and tuppence. But that was not in any way the cost of the book she turned over and over in her hands.

"I did not know I would be this afraid," she said. "Or that I would be ashamed."

Robert stood beside her with his arms crossed. He was a brew of complex emotions, most of them hidden from her.

Number Seven was made of gray stone. Thin, white curtains hung in the windows, so one could see out of but not in. She did not know if anyone were watching her at this moment. "I must reveal myself to these men," she said. "I have the greatest wariness of them. Fouché's organization is the best on the earth, of course – those are the men in France I worked for when I was a spy, you understand – but these British are nearly as good. I have been their enemy all my life. Now I stand in their country not twenty feet from their stronghold. It is a sobering thought. I must leave London immediately when I have passed over this book to them."

"Yes," Robert said.

"You are being silent to me again." The book was getting damp in her hands because they were sweating so. "You have not even asked what it is I do here."

"You're going to bring that book to that house."

"Truly one would think you were a fish, the amount of curiosity in you. What I do here is risk my neck, all so I may become a traitor to my people. It will keep me awake at night for the rest of my life."

"I doubt it." He was a man of many certainties, Robert the smuggler.

"Hah. I will show you." She opened the book and let the pages flow under her fingers. "Look. This is code. Not one I know, and I have no skill in dissecting them. But I do not need to take the code to pieces to know what is in here. When I saw it first in France I saw at once what it must be, written in so many hands, with the numbers in it, and organized just so. This is a report on the ships that Napoleon builds to invade England. When and where and how. It is the work of many cunning men, this book."

"I see."

"You do not see. For you there would be no problem. You are not political You would toss it overboard, or light a fire with it, or give it to those men ..." She glanced once more at Number Seven, Meeks Street. "... in there. It would be all the same for you. For me, matters are less simple. A mile from here is a man named Soulier. A Frenchman. By all the duty of my life, I should take this book to him."

"Why don't you?" Robert crossed his arms.

"Oh ... it is complicated." She scuffed her feet upon the pavement. "I made a promise, for reasons that seemed good at the time. That is some of it. But, in truth ... "

Truth stuck in her throat, as it did, occasionally. She would say it, though. She would admit to herself what she was doing. "I am come here to put a weapon into the hands of the English."

"A weapon?"

"Of a kind. Not a weapon of soldiers. One of politics. Battles do not hinge upon seven ships here and twenty there, most of which the British have been told many times. And they do not know of the false hulls, which will never be completed, and the many ships hidden in the south and ... well, many matters that make this book not so correct as the men who wrote it would like to believe. But I will not tell you these things. They are not good for you to know." She sighed. "The dangerous secrets ... matters of battle plans and troops and supplies. I assure you, they are not in this little book." They were firmly in her brain. But of that she refused to think at all.

"Useless is it?" Robert looked at her without any change of expression. For all he was a smuggler captain and most intelligent, she could be speaking Romany to him.

"Useless to soldiers. This is another sort of weapon. Words can be most powerful, my Robert. Your English diplomats will lay this tally of ships upon the conference table and give the lie to Buonaparte when he claims that he wishes peace and demands concessions." She scowled at what she held, since it tormented her with several hard choices. "This book will be the cat in the pigeons of many dovecotes. The French, themselves, do not know of these ships. The ordinary people. They do not want more war."

"Nobody wants that."

"Perhaps not. But those nobodys do not become traitors this fine morning." She wiped first one hand, and then the other, upon her skirt. "So I will tell the French what Citizen

Buonaparte keeps up his sleeve. And it may be the men of Paris and Lyon and Rouen will see that those hundred ships never sail at all. I have planned this for a week, my betrayal of my country. Now I must do it. When I have finished, I shall be so disgusted with myself I shall not even care if Duval finds me."

"Don't be silly, Anneka."

"You are right. I shall still care and for that I despise myself also." She shrugged. "But this is to make a drama. I have been well trained not to make the dramas. Stay here, mon ami, when I go across and do this thing. These are not people you should involve yourself with."

"I go with you." He said it in a voice not susceptible to argument, being like paving blocks, set closely. So she let him come because she was frightened and wanted him next to her, even if it were dangerous for him, a little. With a man such as Robert beside her she could face even this.

Dull and respectable was written on all the stones at Number Seven Meeks Street which showed that even stones could tell lies. The wide door was placid, as if it were a mouth that had swallowed a thousand secrets and grown fat on them. It was a solidly built house with bars on the windows.

"Go ahead, Anneka," Robert said. "Let's get it over with."

So she rapped loudly, using the knocker which was in the form of a curled rose. In a minute, a boy opened the door, taller than she was, but probably three years younger. Anneka dropped the book quickly into his hands. "A man asked me to bring this to you."

But the boy wasn't looking at her. He was looking past her. At Robert.

Robert took her shoulders, which startled her for it was the very first time he had willingly put his hands upon her. The boy stepped back and Robert pushed her carefully and rapidly across the threshold, into the house, into a room which was a dull, tasteless parlor, stiff with disuse.

"Robert ..." She tried to turn, confused. His hands tightened. "I don't want to be here, Stop it, Robert." The boy locked the door behind them and went to unlock another door on the far side of the parlor.