It occurred to me that this was missing the point somewhat.

So I thought a few scattered thoughts on describing characters.

When you describe a character, you can give a mere list of the obvious. Hair color, eye color, what he's wearing, height, skin tone. But description is more interesting and useful when it serves a secondary purpose. That's thrifty writing.

So we describe our characters and do something else as well. Here's three or four of the several ways to add value to character description:

(ETA, I made that five ways.)

1) You can tell story with description. Make the appearance part of the ongoing action. The description shows result of what has been and intention for what is coming. You could think of it as description propelled by the action.

Not -- 'he had blue eyes'.

So much as -- 'he opened blue eyes, bloodshot from last night's bender'.

Not -- 'she had brown hair, worn long'.

But -- 'She wrestled with wind-tangled brown hair, taming it before she walked into the meeting.'

Not -- He was a huge, rough-looking man with a scar on his face and gray streaks in his hair. He dressed in the respectable, worn clothing a laborer might wear.

Not -- He was a huge, rough-looking man with a scar on his face and gray streaks in his hair. He dressed in the respectable, worn clothing a laborer might wear.But -- He was dressed like a laborer today . . . a big, ugly, thuggish, barely respectable giant in sturdy clothes. His hair was wet and the gray streaks didn’t show. The scar that ran down his cheek was fake. The imperturbable strength wasn’t.

See how the first set of these is a static description. The second is a description that could only be right in that exact moment.

We don't just say, 'this is how Doyle looks', we imply he has looked different in the past. It's not how he happens to look; his appearance is related to the rain outside.

2) We do not just see our fellow; we see him through one specific set of eyes. The POV character adds value, insight and weight to the description. The description turns around and reveals that POV character.

She watched him work for a moment, disquieted by the edged beauty of his face. Lines of his hair fell in thin slashes of black. His lips were strongly marked.

She watched him work for a moment, disquieted by the edged beauty of his face. Lines of his hair fell in thin slashes of black. His lips were strongly marked. She was totally feminine in every movement, indefinably French. With her coloring—black hair, pale skin, eyes of that dark indigo blue—she had to be pure Celt. She’d be from the west of France. Brittany, maybe. Annique was a Breton name. She carried the magic of the Celt in her, used it to weave that fascination the great courtesans created. Even as he watched, she licked her lips again and wriggled deliberately, sensually. A man couldn’t look away.

Could that description of Hawker come from anyone but Justine? Could Annique be seen that way by anyone but Grey, right then, right there, in their prison?

3) Description is not a 'fill in the blanks' list of things we need to convey. It's part of an overall impression. We do not need to be only literal. For the larger portrait, we mix physical details with metaphor and symbol, story history, archetype. Give the hair color, shape of nose, texture of skin. Sure. But also enmesh them in meaning when you do it. Imbed them in the intangibles of the character you are creating.

She had the face of an ardent Viking. Strands of wet hair lay along the spare curve of her cheek, outlining the bones. Her eyes were the color of Baltic amber.

He was young to be captain. Thirty, maybe. He had black hair and a big beak of a nose, and sailor skin, dark and rough, burned by suns that weren't polite and English. Colorful splotches of blood were drying on his shirt. That would be her blood, probably.

4) We use the small details and all the senses.

He couldn't remember the last time he'd wanted a street whore. This one was fresh as a daisy, clean and sweet. She smelled of soap and flowers and spices. Even her fingernails were clean.

ETA: The comment trail, and a comment elsewhere, brought to mind another common use of character description. This uses description for a structural purpose.

5) Let's say you're going to step outside the on-going action, bring the narrative drive to a screeching halt, slow the pacing to molasses, and do some backstorying or philosophizing. Character Description is a great way to segue into the internals you're laying down. Backstory, for instance.

Lookit here. We're fairly early into Black Hawk and I'm filling in the What Has Gone Before column.

“She’ll make it. She’s hard to kill.”

“Many have tried.”

Her hair spread everywhere on the pillow. Light-brown hair, honey hair, so soft and smooth it looked edible. He knew how it felt, wrapped around his fingers. Knew how her breasts fitted into his hands. He knew the weight and shape and strength of her legs when they drew him into her.

A long time ago, she’d shot him. They’d been friends, and then lovers, and then enemies. Spies, serving different sides of the war.

The war was over, this last year or two. Sometimes, he walked outside the shop she kept and looked in. Sometimes, he found a spot outside and watched for a while, just to see what she looked like these days.

The last time they'd exchanged words, she'd promised to kill him. He hadn't expected her on his doorstep, half-dead, running from an enemy of her own.

I have the most dangerous woman in London in my bed.

That's description opening the door to backstory. We go in the order:

a) See her now.

b) Think about her then.

c) Talk about the past.

d) Bring it back to the present. In this case I do that with a line of Internal Monolog.

ETA2: It occurs to me that I didn't really answer the question at the top.

How long can a piece of Character Description be?

Keep it short.

Do not indulge in the flowery crap that readers skip anyhow.

Doesn't matter how beautiful the words are, they have to earned a place in the story with something more than pretty.

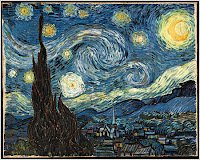

This here is a famous example of what readers skip.

I don't say you can't describe at length. But if you've written more than half a page of Character Description, you should probably go back and reconsider.